It is a solemn day of remembrance. When the sun comes up, heads are bowed, flags fly at half mast, soulful bugles sound The Last Post and volleys are fired.

ANZAC Day is in honour and celebration of all those who fought and died for our country.

A total of 16,697 New Zealanders were killed in WW1. Another 12,000 were lost in the world's most destructive conflict - WW2 - and 37 died on active service in Vietnam.

This is the story of just one of them – a young bomber pilot named Alexander George Herbert, who answered the call to serve and did not come home.

His is one name on Hamilton's Memorial Park cenotaph. Over the next two weeks, and with ANZAC Day looming, The Weekend Sun pieces together the war exploits of an uncelebrated hero, a son and a brother who fought and died for his country.

Flight Lieutenant Alexander George Herbert – Alex to his Mum – stood amongst 54 Blenheim bomber crews gathered for a briefing at RAF Oulton in Norfolk in the early hours of August 12, 1941.

Like most others, he could not believe what he was hearing.

Their mission was to strike the heavily defended Knapsack and Quadrath power stations just outside Cologne, with the bombers required to fly 250 miles over enemy territory in broad daylight without a fighter escort. It was an undertaking described as 'suicidal”.

A Wing Commander at the briefing said it was the only time in his life he saw fellow aircrew grey in the face and shaking. Later that same day, the premonition would play out. The New Zealand pilot was dead. Officially recorded as 'killed on air operations”, his Blenheim bomber was shot down by German fighter planes over the Netherlands on the run home.

As the news was being processed at his home base of RAF Upwood in Cambridgeshire, a letter arrived from New Zealand. It contained a poem by his mother Eva. 'To My Son,” it read, hastily composed and scribbled in pencil on the back of an order of service for a wedding. Perhaps, at that moment, it was what Eva Herbert was wishing for her boy.

'It is just 18 months since you sailed across the sea, and how we wish you home again, Reg, Dad and Me.”

But Flight Lieutenant Alexander George Herbert, 139 Squadron, would never get the letter. He'd never read the poem, would never get home and his mother's wishes would go unfulfilled.

Alexander George Herbert lies in Bergen Central Cemetery, Noord-Holland, Netherlands – plot one, row E, grave 24. He is now just a series of letters and numbers.

The raid was described by the Daily Telegraph in London as 'the RAF's most audacious and dangerous low-level bombing raid”.

'Audacious?” questions Gary McSweeney. 'In other words it was the most stupid bloody air raid ever carried out.”

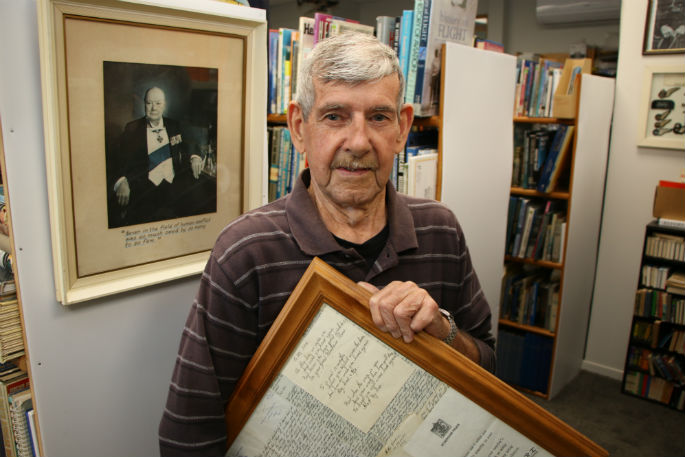

Gary's not related to Alexander Herbert, but all of the airman's personal documents, including his war letters to and from home, ended up in his possession.

It's complicated. Alex's father owned Herbert's Bakery in Hamilton. When Alex was killed, his brother Reg inherited everything. Through a relationship Reg was involved in, one man's war encapsulated in letters, photos and a poem was passed down to Gary McSweeney's stepmother.

'Oh Alex how we miss you, and wish you home again, but know you have great work to do, in your great big Blenheim plane.”

'We were cleaning out her house after she died and there were all these papers and letter,” explains Gary. Although distanced from the man, he didn't want to see the documents end up in landfill. He thought they should be saved and seen, so he mounted a selection in a 50-by-45 centimeter frame and handed them to the library boys at Classic Flyers.

'Documents like these deteriorate if they're not properly cared for,” says George Pocock from the museum library. 'The framed collage would have to be kept out of the light, and therefore out of sight.” And so it was left to The Weekend Sun to tell the story of the picture frame.

There's a note home to mother dated August 4, 1940, from A Flight E.F.T.S. - or elementary flight training school in New Plymouth. 'I finished a very successful months flying by going solo. My heart was ticking, believe me, it was the greatest thrill of my life.”

Just 10 months later, at the Royal Air Force base Upwood in Cambridgeshire, the fresh-faced kid barely out of his teens and looking for adventure, had metamorphosed.

'I am really ready now for operations and am about to take my position in a bomber squadron of the RAF.” Whether by instruction or intuition, he had developed a bloodlust and a deep, abiding loathing of the enemy.

It was declared in that letter of June 4, 1941. 'We are ready to help give back what has been given to us with loads of bombs. I am now in a position to bomb and smash and kill, and I will bomb, smash and kill. And for every drop of blood that was his, he who you loved and I loved, will be paid for with the life of a German. I can do this and I shall.”

The flight lieutenant then explains his anger.

'The world is full of German victims – soldiers, sailors, flying men and common people. There is so much to move the heart, so many folk for whom to pray for in the darkness and in the horror of these evil days. We cannot gauge the suffering inflicted by the Hun, nor count the victims.”

Alexander's first sortie across the English Channel was uneventful. 'Nothing to it,” he wrote. 'We came back unscathed.”

He was almost resentful that he had to hang about for a week before his next mission. 'But, it gave us enough excitement to satisfy everyone.

'We got down onto the sea – about 20ft above it as our operating height. The catch was we passed a squealer boat (a vessel which would alert the enemy to aircraft and shipping movements) and of course when we arrived, everyone was just waiting for us.”

German ground defences opened up – all hell broke loose. 'I had visions about what flak and tracer looked like, but now I know. The air was lousy with tracer.”

The letter is laced with bravado.

'Then two German ME-109s got on to us and (fired a) dozen shots of cannon and machine gun bullets up our backsides. We were left with one engine, and reaching the aerodrome was one thing but landing on it was another, because our oil system had been shot away and the undercarriage and flaps wouldn't work.

'I overshot when we first tried to land and almost took her under a bridge. Next attempt we shot across the grass beautifully – a perfect crash landing.”

That letter was dated July 1941 – and it was probably his last.

The very next month, on Tuesday August 12, Flight Lieutenant G.A. Herbert, RNZAF 401763, took off from RAF Oulton at 09.49 hours. It was a special low-level daylight operation and the targets were the power stations of Koln-Knapsack and Quadrath.

While 139 Squadron hit its targets, the cost was catastrophic.

Of the 54 Blenheims dispatched, 12 were lost, along with six escorting Spitfires. Number 139 Squadron lost three aircraft, with seven airmen killed and two made prisoners-of-war.

Alexander Herbert in Blenheim IV V6261 was close to the Netherlands coast when the bomber was intercepted by German fighters. The aircraft crashed into the North Sea.

A short time later, a typewritten letter arrived at the Herbert Bakery in Hamilton. It's from Buckingham Palace, addressed to F. (Frank) Herbert Esquire, and is a component of the framed collage.

'The Queen and I offer you our heartfelt sympathy in your great sorrow,” it reads. 'We pray that your country's gratitude for a life so nobly given in its service may bring you some measure of consolation.”

It is hand-signed George R.I. – Rex Imperator or King and Emperor – and husband of the Queen Mother.

Herbert and Sergeant George Benton, RAF, were buried in Bergen Central Cemetery, Noord-Holland, Netherlands. The third crewman, Pilot Officer Courtney Claude George, RAF, has no grave. He is commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial, sometimes known as the Air Forces Memorial overlooking the River Thames in Surrey. It is dedicated to some 20,456 lives lost.

This final stanza of the poem to Flight Lieutenant Alexander George Herbert, and written by his mum, Eva Herbert, would be a forlorn hope.

'But when the war is over, And your work has been well done, We know you will come back again, Alex my son.”

Alexander George Herbert, 1918-1941.